Why Does AJK Struggle to Attract Investment?

Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) possesses immense economic potential: a strong overseas diaspora, abundant hydropower resources, fertile land, and a strategically placed geography between Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Yet, despite these advantages, the region continues to struggle with weak investment, limited industrial growth, and a persistent trust deficit.

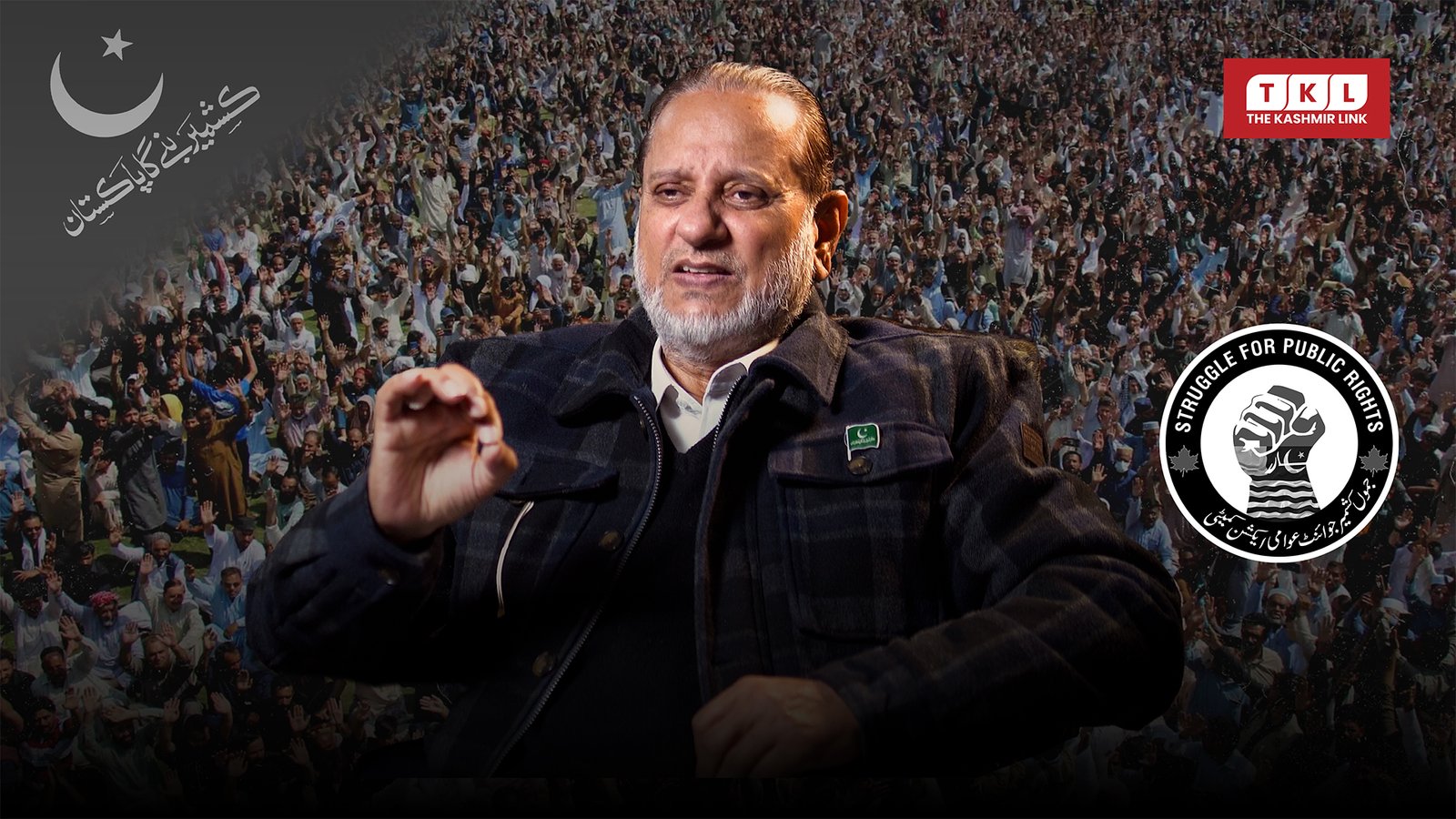

In a wide-ranging interview, Chaudhary Muhammad Saeed—former AJK Minister, renowned industrialist, and former Chairman of the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI)—laid out, with rare candor, the systemic issues preventing Azad Kashmir from moving forward, while also offering a roadmap for reform.

A Business Environment That Discourages Investment

According to Chaudhary Muhammad Saeed, the investment climate in Azad Kashmir is simply not conducive. Legal ambiguity, administrative inefficiency, and a lack of institutional coordination have collectively created an environment where investors hesitate to commit capital.

One of the most glaring challenges is the absence of a clear legal framework for Initial Public Offerings (IPOs). Unlike Pakistan, Azad Kashmir does not have an established mechanism to allow companies to raise capital through the Pakistan Stock Exchange. Although a few companies—such as Kashmir Polytex, Amin Spinning Limited, and a hydel power venture linked with HUBCO—managed to issue public offerings, the process was arduous and riddled with obstacles.

“These legal issues must be addressed if we want serious investment,” Saeed emphasized.

Bureaucracy as a Barrier, Not a Facilitator

A recurring theme throughout the interview was the bureaucratic mindset that prioritizes paperwork over ground realities. Saeed cited personal examples where his operational industrial units were repeatedly declared “closed” on paper, leading to unnecessary notices and threats of plot cancellation.

In one instance, even after submitting an independent consultant’s report explaining the dismantling of a structurally unsafe factory building damaged by the 2019 Mirpur earthquake, official notices continued to arrive—apparently without anyone reviewing the submitted documents.

“This reflects a culture where files are followed blindly, and field verification is ignored,” he noted.

Misunderstanding What ‘Industry’ Really Means

Another critical problem lies in the misinterpretation of the Industrial Act. Saeed pointed out that nowhere does the law restrict industrial plots to smoke-emitting factories. Instead, the Act defines industry as any activity that generates employment, contributes to revenue, and strengthens the economy.

Yet, both political and bureaucratic elites continue to operate under outdated assumptions, discouraging modern service-based and technology-driven enterprises that do not fit traditional industrial imagery.

The Urgent Need for Digitization

In an era where business registration in Pakistan can be completed online within hours, Azad Kashmir still relies on a slow, paper-based system. Company name registration alone can take months, as applications move physically between Mirpur and Muzaffarabad.

Saeed stressed that digitization is no longer optional. Online company registration, automated approvals, and a genuine one-window operation could dramatically improve the ease of doing business and eliminate unnecessary delays.

Financing Challenges and Insecure Leasing Models

Access to finance remains another major hurdle. Industrial plots in Azad Kashmir are typically leased, not owned, which discourages banks from accepting them as collateral. As a result, financing options become limited, valuations remain low, and investors face additional risks.

“These leasing models must be restructured if we want banks to support industrial growth,” Saeed argued.

Losing Ground at the FPCCI

Azad Kashmir’s removal from the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) has further isolated local businesses. A legal challenge questioning AJK’s membership status led to adverse rulings, and the matter is now pending before the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

The consequences have been significant. Access to global trade data, international delegations, policy advocacy, and credibility—previously facilitated through FPCCI—has been severely curtailed.

“Being part of FPCCI gave us visibility, respect, and information. Without it, our business community has been weakened,” Saeed explained.

The Trust Deficit with Overseas Kashmiris

Perhaps the most painful paradox highlighted in the interview is the massive investment by overseas Kashmiris—outside Azad Kashmir. An estimated Rs 350 billion from Mirpur alone is invested in Pakistan’s real estate market.

The reason is simple: trust.

“Investment is shy,” Saeed remarked. “It goes where it feels secure.”

Without legal protection, secure land titles, and transparent governance, diaspora investors prefer safer alternatives like DHA and Bahria Town, where systems work and disputes are minimized.

Urban Chaos and the Failure of Planning

The decline of the Mirpur Development Authority (MDA) serves as a case study in poor governance. Despite being one of the earliest development authorities in the region, MDA failed to revise its master plan for decades, allowing unregulated construction, encroachments, and infrastructure breakdowns.

Saeed called for a comprehensive revision of master plans across all urban centers in Azad Kashmir, strict enforcement of zoning laws, and the establishment of an independent Building Control Authority staffed by qualified urban planners rather than political appointees.

Health, Education, and the Question of Equity

While Azad Kashmir has invested heavily in infrastructure, Saeed argued that quality and equity remain missing—particularly in health and education.

He proposed piloting a health insurance model to ensure equal access for ordinary citizens, citing successful international examples. In education, he criticized outdated curricula, poor facilities, and the absence of regular syllabus revisions, which result in inflated grades but weak competencies.

A stronger partnership between the public and private sectors, he suggested, could raise educational standards and prepare students for global competition.

Tourism, Agriculture, and Untapped Economic Sectors

Tourism alone, Saeed believes, could generate enough revenue to sustain the state—if managed properly. He advocated for public-private partnerships, improved transport, and basic hospitality infrastructure to support domestic tourism.

Beyond tourism, he highlighted opportunities in:

- High-value agriculture (potatoes, tea, floriculture)

- Poultry farming and agro-processing

- Hydropower-linked revenue sharing

- Skill development and vocational training aligned with global markets

A Vision Rooted in Governance and Trust

Ultimately, the interview returned to one core principle: governance.

Without legal clarity, institutional reform, digitization, and political consensus on a National Business Agenda, progress will remain elusive. Saeed emphasized the need to move beyond regionalism, populist politics, and short-term fixes, and instead offer the public a clear vision, timeline, and destination.

“Human life and investment both flee insecurity,” he concluded. “If we can protect these two, there is no reason Azad Kashmir cannot prosper.”

Editor’s Note:

This article is based on a detailed interview with Chaudhary Muhammad Saeed and reflects his views and policy perspectives on governance, investment, and economic reform in Azad Kashmir.